Archive for August, 2023

A Tale of Three Bidirectional Level Shifters

Level shifters, voltage translators: whatever you call them, these devices are very handy when interfacing 5V and 3.3V logic for devices that aren’t 5V-tolerant. The 74LVC244 has long been my go-to solution for unidirectional 5V to 3.3V level shifting, and for 3.3V to 5V I’ll typically do nothing, since the 5V inputs generally work OK without shifting. But sometimes you need bidirectional level shifting with automatic direction sensing, and you may also want to step up those 3.3V signals to a full 5V. Enter three solutions from Texas Instruments: TXB0104, TXS0104, and TXS0108. These three chips all provide 4 or 8 channels of bidirectional level shifting with auto direction sensing, and at first glance they all seem very similar. But as I recently discovered, under the hood you’ll find significant differences in how they work and the types of applications they’re best suited for.

TXB0104

TI describes this chip as a “4-Bit Bidirectional Voltage-Level Translator With Automatic Direction Sensing.”

This TXB0104 4-bit noninverting translator uses two separate configurable power-supply rails. The A port is designed to track VCCA. VCCA accepts any supply voltage from 1.2 V to 3.6 V. The B port is designed to track VCCB. VCCB accepts any supply voltage from 1.65 V to 5.5 V. This allows for universal low-voltage bidirectional translation between any of the 1.2-V, 1.5-V, 1.8-V, 2.5-V, 3.3-V, and 5-V voltage nodes. VCCA must not exceed VCCB.

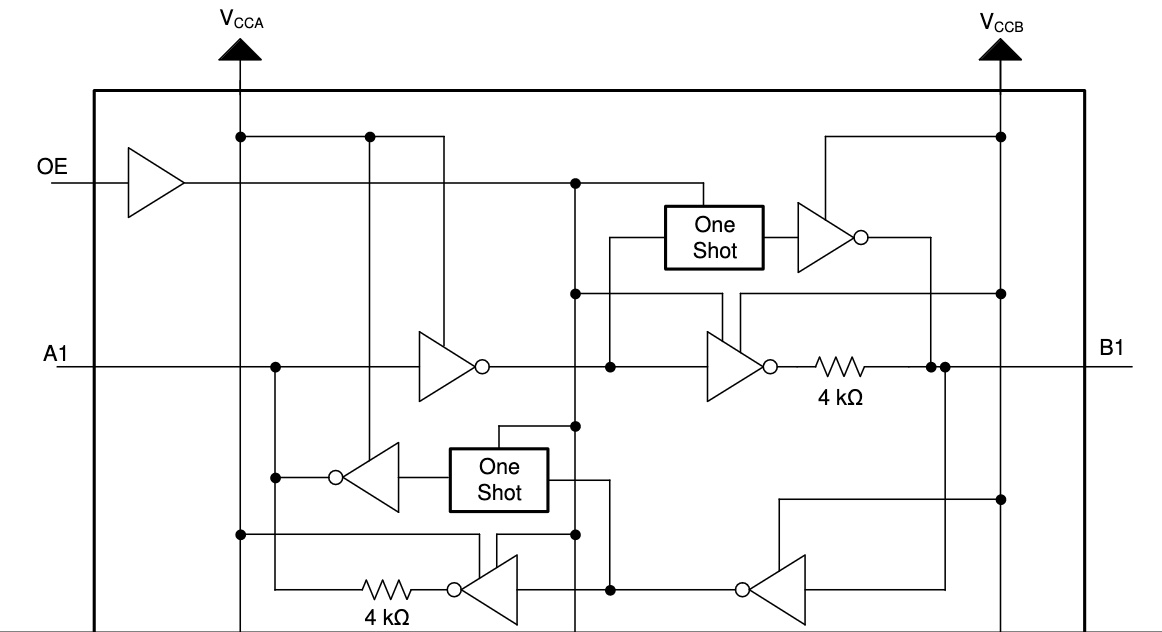

Power VCCA with 3.3V, power VCCB with 5V, and then it just works without any further configuration. Signals on pins A1..4 are propagated to pins B1..4 and vice-versa, while performing level shifting. But how? Scroll down to page 16 of the datasheet to find this block diagram of a single level shifter channel:

It’s complicated, but the most important thing here is that when the pins are treated as outputs, they’re actively driven to a high or low voltage with a pair of inverters. The output drive current is supplied by the TXB0104, through these inverters. When the pins are treated as inputs, the input signal is supplied to another inverter. In many ways it’s like the 74LVC245 except the direction is sensed automatically.

Elsewhere in the datasheet, it mentions a maximum data rate of 100 Mbps when VCCA is at least 2.5 volts.

TXS0104

Change a single letter in the part name, and you get TXS0104. What’s different? TI describes it as a “4-Bit Bidirectional Voltage-Level Translator for Open-Drain and Push-Pull Applications”. That sounds awfully similar to the TXB.

This 4-bit non-inverting translator uses two separate configurable power-supply rails. The A port is designed to track VCCA. VCCA accepts any supply voltage from 1.65 V to 3.6 V. VCCA must be less than or equal to VCCB. The B port is designed to track VCCB. VCCB accepts any supply voltage from 2.3 V to 5.5 V. This allows for low-voltage bidirectional translation between any of the 1.8-V, 2.5-V, 3.3-V, and 5-V voltage nodes.

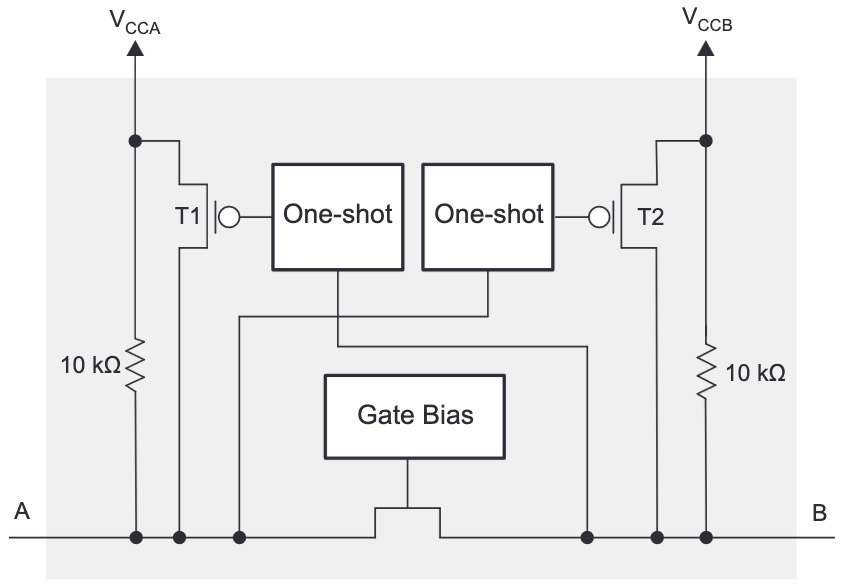

That’s virtually identical to the text in the TXB datasheet. But the block diagram of a single level shifter channel reveals something that’s completely different!

The chip uses a pass transistor to connect the A and B pins. It’s the same basic concept as the classic single-transistor level shifter, commonly built with a BSS138 MOSFET, whose theory of operation is described in section 2.3.1 of this Philips application note. The drive current for low signals is supplied by the external device that’s driving the pin, and not by the TXS0104. For high signals, there’s a 10K pull-up resistor. The TXS0104 improves on the classic design by adding one-shots that can accelerate rising edge times compared to what’s possible with the pull-up alone.

This type of level shifter is best suited to open-drain applications like I2C communication, but can also be used with push-pull input signals that are actively driven high and low. The datasheet mentions a maximum data rate of 2 Mbps for open-drain and 24 Mbps for push-pull.

I won’t be using I2C, but I will be relying on the ability to put signals in a tri-state (floating) condition, and that’s something TXB0104 can’t really do. Yes the TXB has an enable input that can place the whole chip into a tri-state condition, but it requires a separate enable signal from my 3.3V microcontroller, and it doesn’t allow for individual signals to be tri-stated. But the TXS0104 supports this quite well. If a pin on the A side is tri-stated and left to float, the 10K pull-up will lift it to 3.3V, which turns off the pass transistor. Another 10K pull-up on the B side pin lifts it to 5V. This is a weak pull-up, so other devices on the 5V side can actively drive the signal high or low without problems. The TXB0104 can’t do this since it’s always actively driving the pin.

At least this is my analysis based on the datasheets, but I’m happy to be proven wrong here. Perhaps the TXB might also work if the A side is tri-stated and it auto-configures the data direction from B to A. As far as I can see, though, the TXS0104 looks like the best choice for my needs. 24 Mbps (with inputs driven push-pull) should be plenty fast enough, since my application only requires 1 or 2 Mbps at most.

TXS0108

Many people would assume the TXS0108 is simply an 8-bit version of the TXS0104, with twice as many channels but everything else the same. The datasheet seems to support this, calling it a “8-Bit Bi-directional, Level-Shifting, Voltage Translator for Open-Drain and Push-Pull Applications”:

This device is a 8-bit non-inverting level translator which uses two separate configurable power-supply rails. The A port tracks the VCCA pin supply voltage. The VCCA pin accepts any supply voltage between 1.4 V and 3.6 V. The B port tracks the VCCB pin supply voltage. The VCCB pin accepts any supply voltage between 1.65 V and 5.5 V. Two input supply pins allows for low Voltage bidirectional translation between any of the 1.5 V, 1.8 V, 2.5 V, 3.3 V, and 5 V voltage nodes.

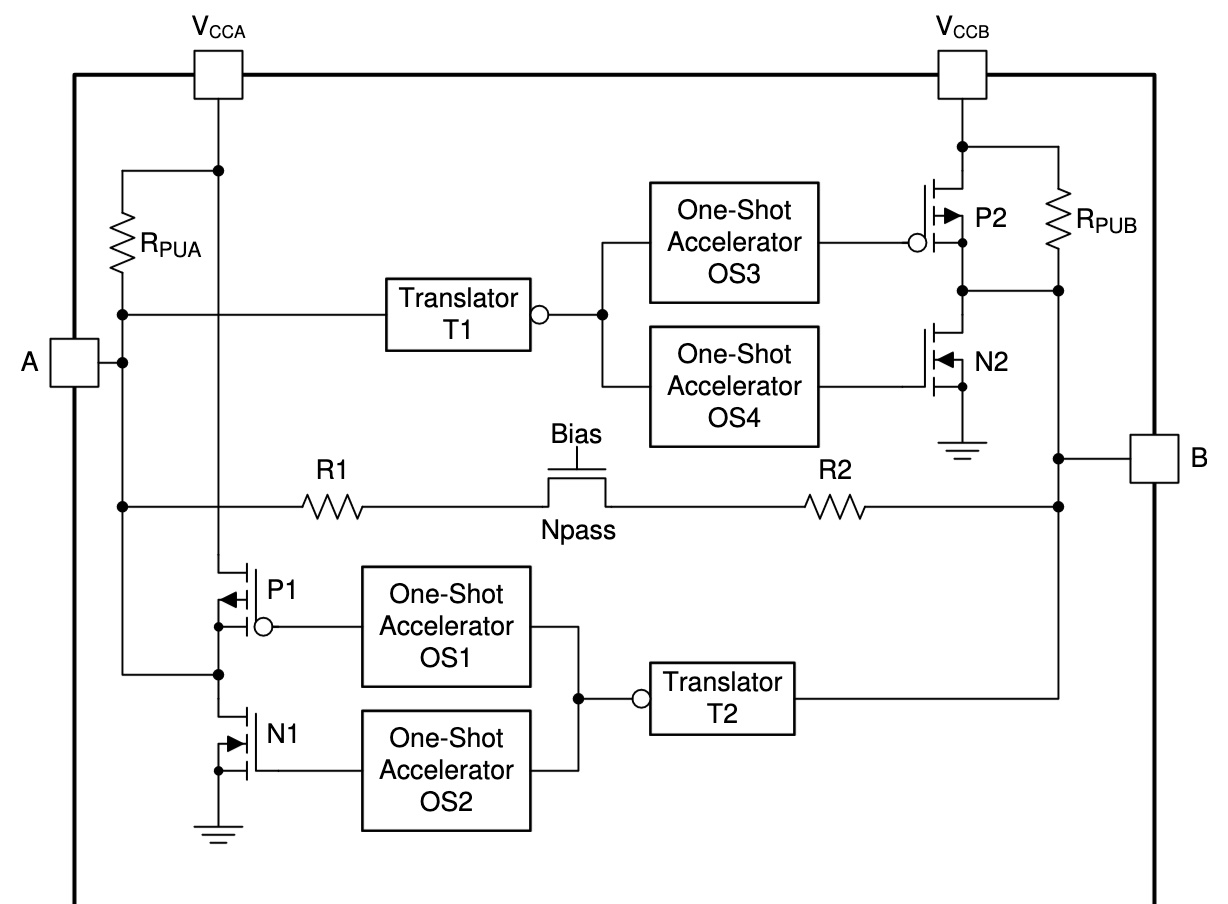

But once again, the block diagram of a single level shifter channel reveals something that’s quite different from either the TXB0104 or TXS0104:

It’s conceptually similar to a TXS0104, but with many additions that are designed to support faster signal rates. Instead of a single one-shot to accelerate rising edges, there are separate one-shots to accelerate both rising and falling edges. The pull-up resistors aren’t fixed at 10K ohms anymore, but dynamically change their values depending on whether the signal is rising or falling. There’s also some extra resistance in series with the pass transistor.

The datasheet mentions a maximum data rate of 110 Mbps for push-pull, which is much faster than 24 Mbps on the TXS0104. Faster is better, right? Maybe not. The TXS0108 datasheet also contains a warning that’s not found in the TXS0104 datasheet:

PCB signal trace-lengths should be kept short enough such that the round trip delay of any reflection is less than the one-shot duration… The one-shot circuits have been designed to stay on for approximately 30 ns… With very heavy capacitive loads, the one-shot can time-out before the signal is driven fully to the positive rail… Both PCB trace length and connectors add to the capacitance of the TXS0108E output. Therefore, TI recommends that this lumped-load capacitance is considered in order to avoid one-shot retriggering, bus contention, output signal oscillations, or other adverse system-level affects.

Sparkfun sells a TXS0108 level shifter breakout board, and their hookup guide mentions struggling with this problem:

Some users may experience oscillations or “ringing” on communication lines (eg. SPI/I2C) that can inhibit communication between devices. Capacitance or inductance on the signal lines can cause the TXS0108E’s edge rate accelerators to detect false rising/falling edges.

When using the TXS0108E, we recommend keeping your wires between devices as short as possible as during testing we found even a 6″ wire like our standard jumper wires can cause this oscillation problem. Also make sure to disable any pull-up resistors on connected devices. When level shifting between I/O devices, this shifter works just fine over longer wires.

The TXS0108E is designed for short distance, high-speed applications so if you need a level shifter for a communication bus over a longer distance, we recommend one of our other level shifters.

This statement confuses me a bit. At first it says even a 6 inch wire is problematic, then it says it works just fine over longer wires, before concluding that you should choose a different solution if you need communication over a long distance. For disk emulation applications I may need to drive signals on a cable that’s several feet long. My take-away is that the TXS0108 is much more fiddly to use successfully than the TXS0104, and is prone to oscillation problems when circuit conditions aren’t ideal – which will probably be the case for me. Since I don’t need 110 Mbps communication, there’s no compelling reason for me to use the TXS0108 except the minor space and cost savings compared to a pair of TXS0104’s. I can run at slower speeds with a TXS0104 and hope to minimize problems with oscillations.

My conclusion? When selecting parts, read the datasheet, the whole datasheet. All three of these chips have nearly identical titles and descriptions on page 1, and it’s only after digging further down that their significant differences become apparent.

Read 3 comments and join the conversationMactoberfest: October 14 Bay Area Classic Macintosh Meetup, Expo, Repair Clinic, Swap Meet

UPDATE: See newer Mactoberfest info here. It even has a fancy logo now.

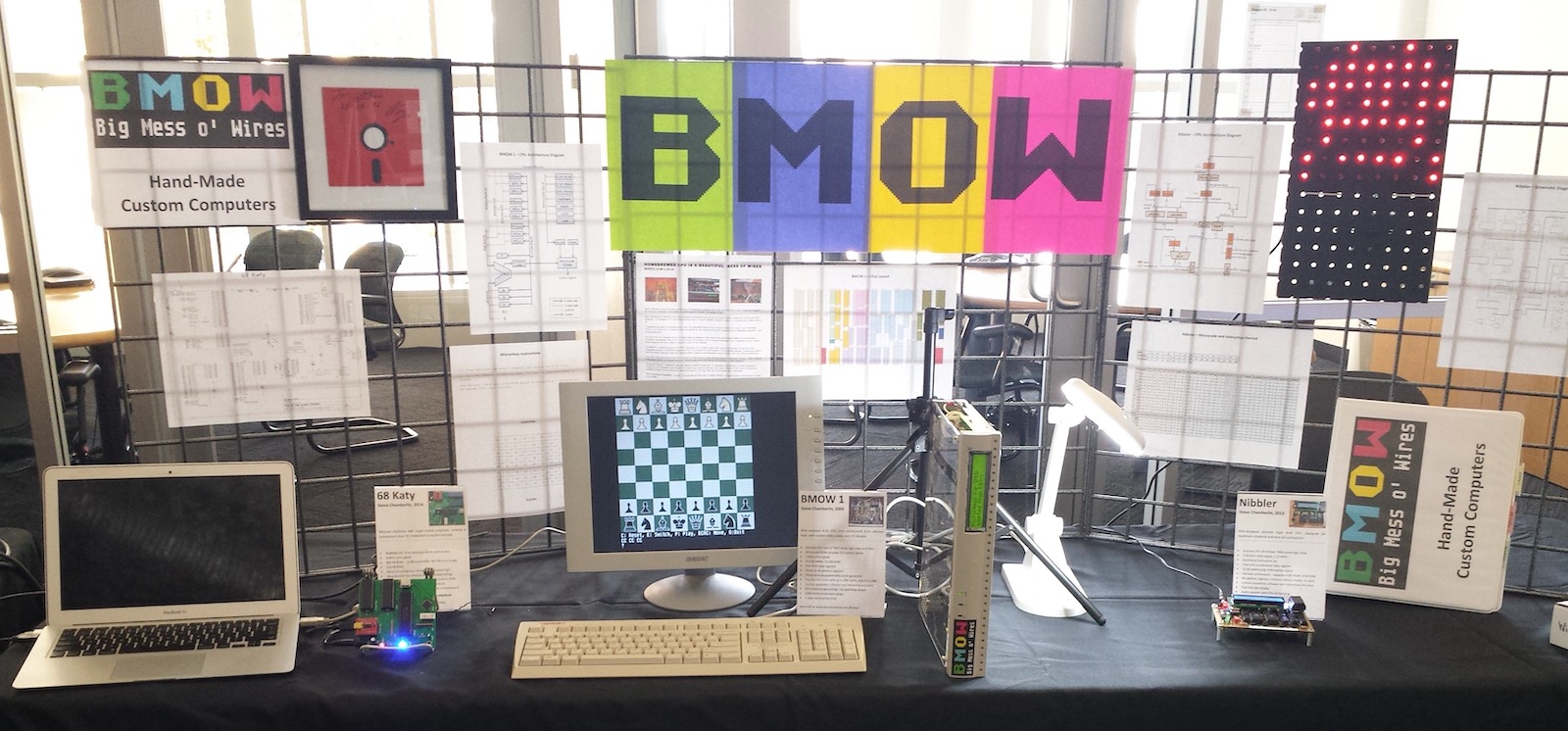

Somebody stop me! On Saturday October 14 from 11am to 5pm, Big Mess o’ Wires invites you to the 1st Annual Mactoberfest San Francisco Bay Area Classic Macintosh Meetup / Mini-Expo / Repair Clinic / Swap Meet / Open House / LAN Party / Hangout. Bring your classic Macintosh collection, your tools, your extension cords, your Localtalk cables, and all your best nerd toys. If you want to bring some Apple II or other vintage computers too, I won’t stop you. I’ve rented a room for 50-ish people, furnished with tables and chairs, and the rest is up to you:

- Mingle and chat. Stump the crowd with Macintosh trivia. How many of the signatures on the inside of the Mac 128K’s case can you name?

- Hardware showcase. Demo your interesting computers, peripherals, software, and vintage tech. I heard a rumor that some never-released classic Apple prototypes might be there.

- Repair broken equipment. Bring your soldering iron, multimeter, or scope. We’ll crowd-source some fixes.

- Beam some notes to other Newton users with IR. When else will you have a chance to do that?

- Play classic networked games like Bolo and Spaceword Ho!

- Buy, sell, trade, or donate vintage equipment. Find that one weird part you’ve searched for since 2008.

- Stock-up on BMOW’s vintage computer products. Yeah I’ll have stuff available for sale, but that’s not the point of this event.

- Debate whether the Newton was just ahead of its time, or was actually hot garbage.

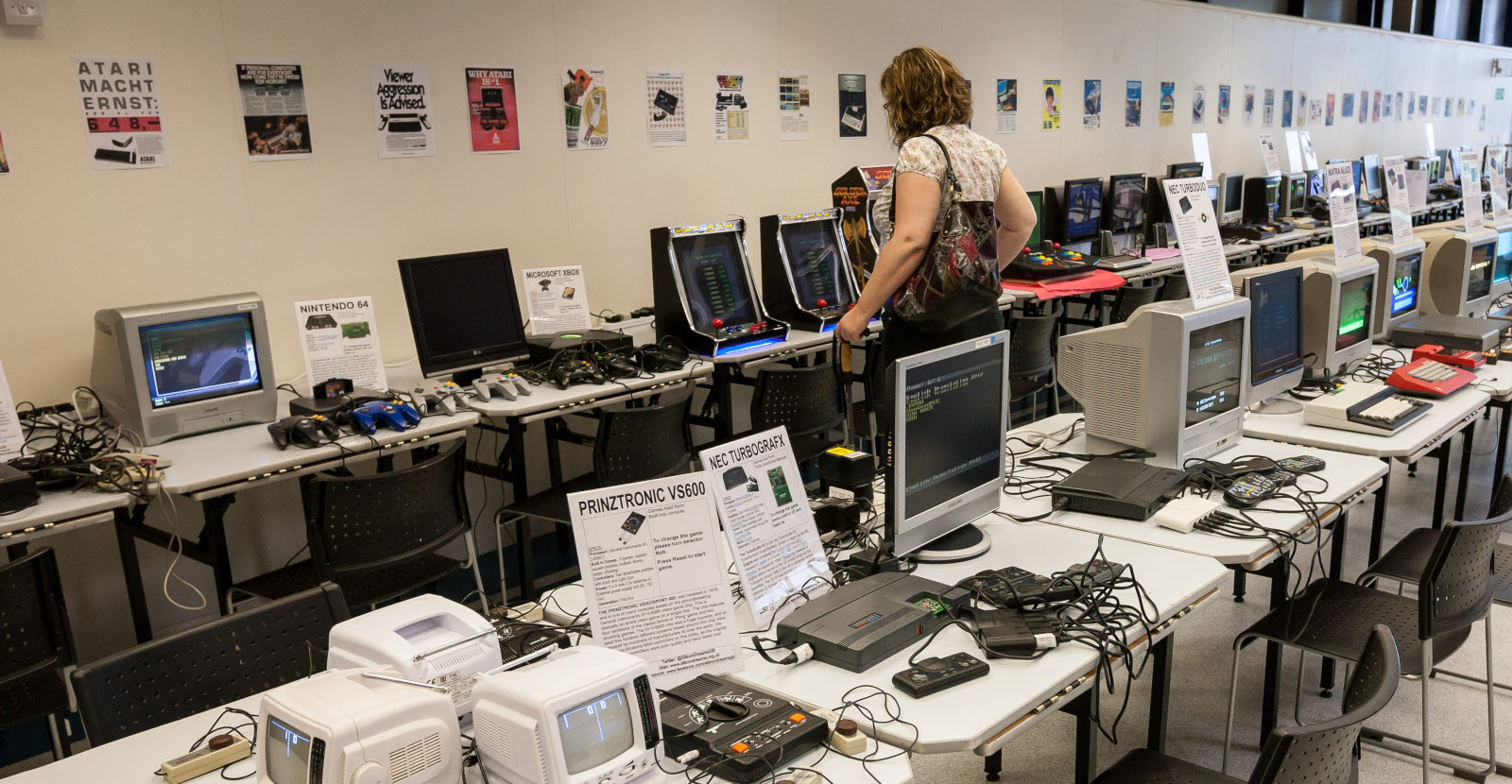

This will be fun, but set your organizational expectations low. It’s a large rented room with lots of tables and chairs, hosted by Big Mess o’ Wires. The rest is up to you. The photo above is from a computer festival in Europe, and is much better coordinated than the chaos we’ll probably have. Don’t expect a highly-polished and curated event with fancy exhibits, a speaker series, and mad prizes. Don’t expect to wander through museum displays without talking to anybody. This is a low-key participatory event built on your own involvement and whatever goodies we collectively bring to play with.

Where

I’ve rented a large room near my home in Belmont California, in the middle of the San Francisco peninsula. Belmont is near Highway 92 and is roughly equidistant from San Jose and the South Bay, San Francisco and points north, and Oakland, Berkeley and the East Bay. If these words mean nothing to you, then you’re not in California and you’re too far away, sorry.

What to Bring

Please don’t forget to bring your electric extension cords! I’m not the AV department and I won’t be providing any electric cords. The room will have plenty of 6 x 3 foot tables and chairs, and copious electric outlets, but the closest outlet might not be near your table. There’s a hardware store half a mile away, if you need more extension cords on the day of the event. Also bring your classic Macintosh and other vintage computers, items to sell or trade or repair, tools for making repairs, and networking equipment if you want to LAN play. Don’t forget to put your name on your power cords and all your equipment, so it doesn’t get confused with somebody else’s stuff.

Attendance

I expect to have between 30 and 100 people. If we have more than 50 who are interested, I’ll need to start making table assignments. If this event goes viral and 500 classic Macintosh fanatics show up, plus Tim Cook and all the members of the original Macintosh dev team, we’ll have a problem because there’s a hard maximum of 100 people for the room.

RSVP here (in the Google Form) if you’re maybe, probably, or definitely planning to attend. This will help me keep track of who’s bringing what hardware, and the likely overall attendance level. The street address within Belmont is on the RSVP form.

If it looks like we may exceed 100 people then I’ll close the RSVP. Don’t be that sad person who’s turned away at the door (although you might start a Classic Macintosh tailgate party in the parking lot).

1st Annual Bay Area Classic Macintosh Meetup / Expo / Clinic / Swap-Meet

Hosted by Big Mess o’ Wires

Saturday October 14, 11:00am to 5:00pm

Belmont, California

in the “Fireplace Room”

(event address is on the RSVP form)

See you there, and don’t forget to RSVP!

RSVP here for the Classic Macintosh Event

Read 8 comments and join the conversation

Wombat Firmware Update: Hardware Mouse Scaling

The BMOW Wombat enables the use of USB mice with ADB computers, such as classic Macintosh and Apple IIgs systems. It’s a great feature, but sometimes the mouse tracking speed appears too fast or too slow for convenient use, even after making adjustments in the host OS’s mouse control panel. Firmware version 0.3.9 introduces a new Wombat feature to help: hardware mouse scaling.

With each long-press of the USB mouse wheel button (longer than half a second), the Wombat increases the mouse tracking hardware scale by a factor of 2. This scale is in addition to any mouse scaling that’s applied in the host OS’s control panel. The available scaling factors are 1/2/4/8/16x. For the Razer Basilisk v2 mouse shown in the video, I found that 8x scaling felt about right, but your tastes may be different.

Firmware 0.3.9 also disables an error-checking feature in the Wombat’s parser for USB HID report descriptors, because some USB devices have a minor error in their report descriptor, including this Basilisk mouse. The descriptor uses a sort of universal grammar for HID devices to describe what they do and what kind of data they can send and receive. The Basilisk has an error in its report descriptor where it specifies a maximum possible value of 572 for a report item that’s only 8 bits in size. The Wombat report parser was seeing this error and rejecting the whole device. Disabling the error check enables the Basilisk to work with no ill effects. This change may also “fix” some other USB mice and keyboards that previously weren’t recognized by the Wombat.

Download the latest Wombat firmware now, and let me know how it works for you.

Read 1 comment and join the conversationSearching for Paul C. Pratt

Paul C. Pratt is the man behind the Gryphel Project, an ambitious software and documentation effort to preserve and extend classic 68000-based Macintosh computers. He’s the author of the wildly-popular Mini vMac emulator, as well as other great tools like disassemblers and ROM utilities. Paul’s been a pillar of the classic Macintosh community for decades. Although I’ve never met him, I’ve exchanged many emails with Paul over the years, and he’s always been helpful.

Paul has gone missing. Not missing in the sense of a family emergency and police search, but missing for over two years from the classic Macintosh community where he’s been an active member for so long. His Gryphel Project site is still up, but there have been no new posts there since April 2021. He hasn’t appeared anywhere else online either, and he’s not responding to emails, nor to messages sent through community forums where he’s a member. Paul doesn’t have much social media presence, and nobody’s sure of his real-world address or phone number.

Maybe some family emergency or health crisis has demanded Paul’s attention since 2021? Maybe he simply got burned out on classic Macintosh topics, and decided to abandon his online identity and walk away from it all? For the past year, concerned members of the community have attempted to get in touch with Paul through various ways online and real-world to confirm he’s OK, or to ascertain what might have happened to him. They’ve not been successful, which is frustrating and sad.

I sincerely hope that Paul’s sitting in a sunny meadow somewhere, enjoying a lovely day and not giving any thought to crusty old Macintosh computers. But with every passing day that he’s not heard from, we all fear the worst. If he’s died, it’s entirely possible that Paul’s heirs might not think or care to tell anybody outside of his immediate family and friends. From his bio we know that Paul was born in 1969 or 1970, which makes him about 52, and the same age as me. That’s not old, but it’s a cautionary reminder that none of us live forever.

Hearing Paul’s story has motivated me to draft a continuity plan for BMOW, in case of my sudden unexpected disability or death. I’ve made arrangements to ensure the blog and the store would be gracefully wound down, and product designs would be transferred to responsible hands to make sure that nothing important is lost.

Read 6 comments and join the conversation