Archive for April, 2022

Learn Morse Code for Fun and Profit

Today is Morse Code Day! You might be surprised to learn that CW (the modern term for Morse) is still widely used in certain corners of the amateur radio universe, not for nostalgia reasons, but because it’s still the best solution to a particular problem. If you want a human-mediated communication method with low transmitter power requirements, good for portable use, and with a very narrow bandwidth (to avoid overlap or interference with other signals), then Morse is your answer. There are plenty of companies making new CW transceivers, like this Mountain Topper series. Maybe their slogan should be “Morse: not dead yet.”

For the past several weeks I’ve been hard at work attempting to learn Morse, spending time each day with trainer software to practice decoding and sending. It’s hard. It doesn’t take too long to learn the dash-dot patterns of the 40-something letters, numbers, and symbols, but it’s hard to be fluent enough to mentally decode them quickly and without conscious thought. Unlike reading a book in a foreign language, you can’t stop and go back over a section where you had trouble. If you ever need to pause and think “what does dash-dot-dash-dash mean again?” then you’re dead. You just need to practice and practice until dash-dot-dash-dash innately sounds like Y in your head, just as much as a spoken word does.

A few decades ago, most people learned Morse by starting at a slow speed about 5 words per minute, which was once the speed requirement for a Novice radio operator’s license in the United States. But at that speed, you can consciously count the dashes and dots, and you naturally construct a lookup table inside your head. You think 1-1-2, oh that’s a Y. But this turns out to be a handicap when you attempt to go faster, and conscious access to a mental lookup table simply can’t go fast enough. The most recommended learning method today is to start learning letters at 18 to 20 wpm, where you can’t easily count the individual dashes and dots anymore, but you learn to recognize the rhythm of each letter, like a snippet of music. But to avoid becoming overwhelmed, extra space is inserted between each letter so the overall average rate is still 10 wpm or less.

Experienced CW operators tell me that learning to send Morse is actually easier than learning to receive and decode it. I’ve been practicing receiving for several weeks, but only just started sending practice a few days ago.

The technology used for sending Morse has changed over the decades. In old movies you see people making tap-tap-tap gestures on a single lever, that’s called a straight key. These aren’t used much anymore, but they’re easy to understand. As long as the key is held down, the radio emits a tone, and the operator has full control over the speed and relative duration of dashes and dots and the gaps between them. This allowed operators to develop a distinctive keying style called a “fist”, which others could use to recognize them even if they weren’t explicitly identified. For example, an operator might have a habit of slightly rushing the last dot in R, or using a particular uneven spacing between the elements of C.

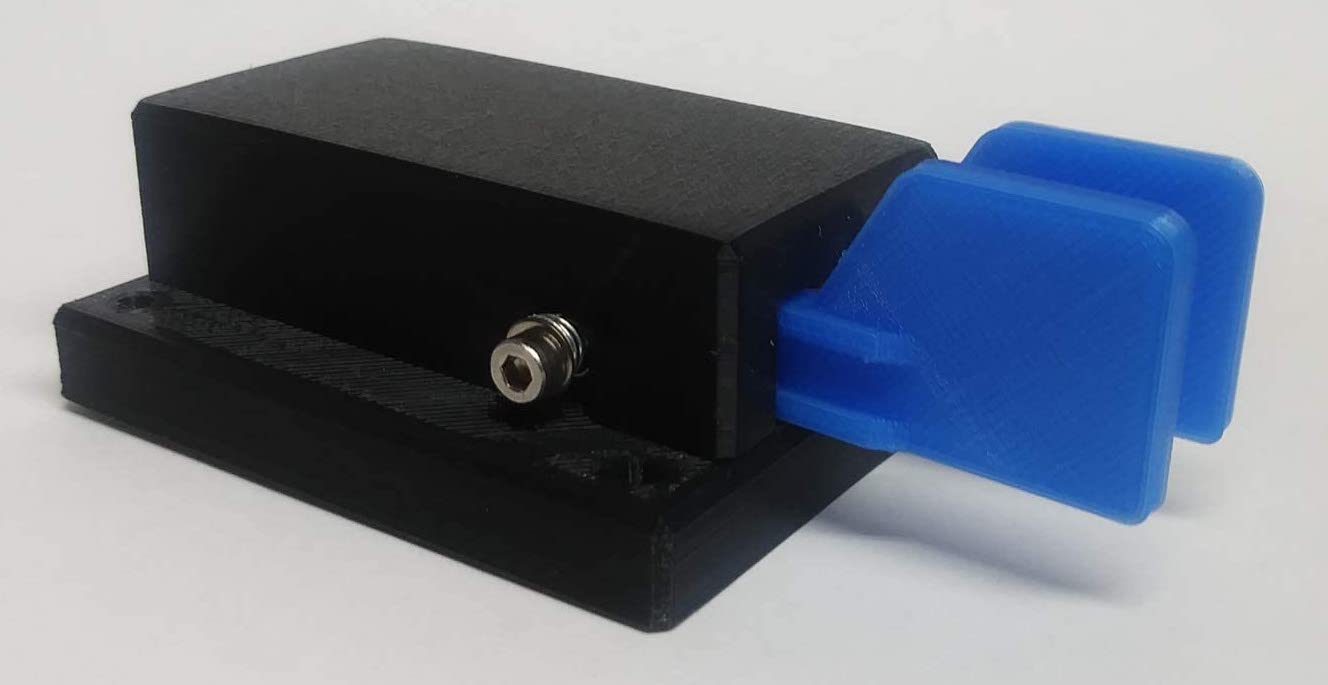

Today most CW operators use a device called a paddle, along with an electronic keyer. The paddle has two levers that are pushed horizontally rather than vertically, one paddle for dashes and one for dots. A circuit in the electronic keyer emits a perfectly-timed series of dashes or dots for as long as the corresponding paddle is pushed. There’s also a simple form of “type ahead”. If you push the dot paddle while a dash is being transmitted, the keyer will emit the dot after the dash is finished, with exactly the right gap between them.

VBand is a fun web-based tool for experimenting with Morse code along with other beginners. You can use keyboard keys as if they were the levers on a paddle, then jump into a chat room and have a horribly fractured conversation with a stranger.

An odd bit of trivia: the original code developed by Samuel Morse in 1838 is not what’s used today. That code was retroactively named American Morse Code, after the rest of the world adopted a different version. American Morse is rather strange, and is now more-or-less extinct. Everybody today uses International Morse Code. Score one for standardization.

Read 4 comments and join the conversationIntentional Unintentional RF for Sneaky CW Transmissions

An unintentional radiator is a device that emits radio frequency signals, even though it’s not intended to. Usually this happens as a result of poor circuit design or inadequate shielding, and it’s a problem. For sneaky purposes, an unintentional radiator can also be used intentionally to send a weak radio signal that carries real information, instead of just causing interference. For example, see this DDR SDRAM hack that uses carefully-timed memory accesses to transform memory bus traces on the PCB into a WiFi antenna, transmitting signals from air-gapped computers.

I’ve started wondering if a simpler version of the same idea could be used to send Morse code transmissions on standard ham radio bands. For example, say you have an Arduino with a built-in LED. If you use PWM to toggle the LED on and off at 7.4 MHz, and tune a radio that’s sitting next to the Arduino to 7.4 MHz CW, I think you would hear a steady carrier. By programmatically enabling and disabling the PWM, you could create the dots and dashes of Morse code. It might take a little experimentation to discover which traces on the Arduino PCB radiate best, at what frequencies. But this kind of thing seems to happen often enough by accident, so it maybe wouldn’t be hard to do it on purpose.

A more interesting avenue would skip the Arduino, and work directly on a typical computer. Is there some Javascript code you could write that would abuse the hardware APIs to enable and disable some oscillator on the computer whose frequency is in a standard ham band, that might unintentionally radiate a very weak signal, and that can be programmatically switched on and off to create Morse? For example, you can do USB HID stuff now through Javascript, and a USB cable might make a nice antenna. Or maybe try some carefully-timed sequence of RAM or SSD access. Or somehow abuse the camera API or anything else that would involve switching signals in the tens to hundreds of MHz range.

The end result could be like magic: just visit a web page in your browser, then tune a nearby radio to the right frequency, and hear a Morse code message. It would be like playing music with floppy drives, except at radio frequencies. Is there any existing proof-of-concept for an idea like this?

Read 4 comments and join the conversationDon’t Cook Yourself With RF Energy

I’m getting ready to install a radio antenna on my home’s roof, and hoping to avoid hurting myself or anybody else in the process. While falling off the roof may be the most obvious risk, a less obvious concern is the radio frequency energy from the antenna when it’s transmitting. Is this something to worry about it? How much RF exposure is too much? Let’s take a look.

Electromagnetic waves in the radio frequency spectrum are what’s called non-ionizing radiation. They don’t have anywhere near enough energy to knock electrons loose from an atom or molecule. Unlike x-rays or gamma rays, they can’t cause radiation sickness, genetic damage, or cancer. The primary human risk from RF is heating up tissue – it can cause burns or literally cook you. This is how a microwave oven works, for example. There’s no risk for a human near an antenna that’s only receiving, but you need to be careful any time the antenna is transmitting. The risk depends on several factors, some obvious ones and some less obvious:

- Transmitter power – Higher power means higher RF energy levels.

- Distance from the antenna – The closer you are to the antenna, the higher your exposure.

- Transmitter duty cycle – Exposure is averaged over a period of several minutes. A 100 watt continuous transmission creates equivalent exposure to a 200 watt transmission alternating 1 minute on, 1 minute off.

- Height above ground – Radio waves can bounce off the ground and reflect back up, concentrating more of the total energy in a single spot.

- Proximity to buildings and nearby objects – Radio waves can also bounce off buildings, creating a similar effect to ground bounce.

- Antenna type – RF energy isn’t radiated equally in all directions. Some antenna types concentrate more energy at low elevation angles close to the horizon, or in specific directions. A human in the high-concentration zone will get higher RF exposure.

- Transmission frequency – The human body is most efficient at absorbing RF energy in the 30-300 MHz frequency range, so the risk is higher for radio transmissions in this range.

- Transmission mode: voice, digital, or Morse code – A 100W-rated radio that’s continuously transmitting may not be outputting 100W continuously; it depends on the transmitted signal. Continuous wave (CW or Morse Code) transmissions come closest to reaching the advertised power all the time. FM voice does too. But AM voice and single sideband (SSB, a type of AM) transmissions have an instantaneous output power that depends on how loudly you’re speaking at that moment. If you’re silent, the power is effectively zero.

In the United States, the FCC’s OET Bulletin 65 Supplement B describes the maximum permissible exposure or MPE limits for RF electromagnetic fields, and some methods used to calculate the exposure. MPE limits are defined in terms of power density (units of milliwatts per centimeter squared: mW/cm 2), electric field strength (units of volts per meter: V/m) and magnetic field strength (units of amperes per meter: A/m). Fortunately you don’t need to understand the details of all this, and can simply use their data tables to determine how far away people must be from the antenna in order to stay safe.

Controlled and Uncontrolled Exposure

The FCC sets two different MPE limits, for controlled and uncontrolled exposure. The controlled limits are higher, and they apply when people know they’re close to an antenna and have been trained to understand the potential risks. Typically this would mean a workplace setting, but controlled exposure limits also apply for licensed amateur radio operators and their families, assuming they’ve had RF safety training. The uncontrolled exposure limits apply to the general population, who may be completely unaware of the risks or who don’t know there’s an antenna present.

I don’t understand the reasoning behind this. Just because someone knows there’s an antenna, and has received RF safety training, how does that make their body less susceptible to injury from RF energy? If you can explain this, please do. For my home, I’m choosing to use the stricter uncontrolled general population exposure limits even though I’m not required to.

Doing the Math

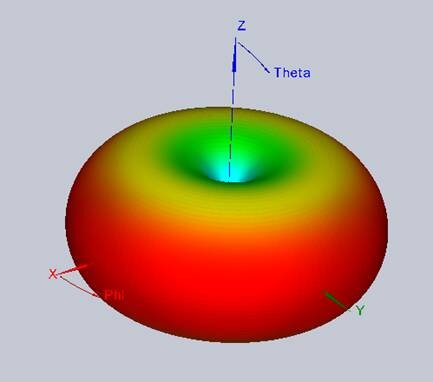

Let’s look at some specific numbers. I’m installing a dual-band VHF/UHF antenna that’s a clone of the Diamond X30. It transmits at about 145 MHz for VHF, or about 450 MHz for UHF. It’s a vertical antenna with an omnidirectional radiation pattern in azimuth, but the pattern is squished vertically. More energy is radiated straight out toward the horizon, and less energy up or down where there’s usually nobody to talk to anyway. The radiation pattern is like a flattened donut, with the antenna centered at the hole in the middle.

This particular antenna has a gain of 3.0 dBi for VHF and 5.5 dBi for UHF. This gain isn’t true amplification, it’s just a measure of how concentrated the RF energy is in the direction of interest relative to a hypothetical reference antenna. The “gain” comes from the degree of squishing in that radiation donut.

The radio uses standard FM modulation, and has a maximum output power of 25 watts, although most of the time I’ll probably run it at lower power.

Marshalling all this information, we could use the data tables in the FCC bulletin to estimate the minimum safe distance from the antenna for uncontrolled exposure. Fortunately several people have created easy-to-use calculators based on the FCC data, so let’s use this RF exposure calculator from Paul Evans VP9KF. Plugging in 25 watts, 3 dB gain, 3 meter distance, 145 MHz, with ground reflection, the calculator tells us 3 meters is safe and 2.27 meters (7.45 feet) would be the minimum distance. With 5.5 dB gain at 450 MHz, the safe distance is 2.47 meters (8.1 feet).

Going the Distance

8.1 feet isn’t a huge distance, but neither is it small. I probably don’t want to put that antenna directly outside the window from where I’ll operate the radio, or on the roof directly overhead that spot. Nor should it be anywhere that somebody might come and sit within 8 feet of it for an extended period of time. This might not be easy to achieve.

It’s important to understand that this 8.1 feet number is the most pessimistic and conservative number. It assumes my radio is continuously transmitting 100 percent of the time, which it certainly won’t be. It assumes the 25W from the radio is completely radiated as RF energy, when in fact some energy will be lost in the transmission cable to the antenna. It assumes the worst possible ground bounce. And it assumes a person is in the main lobe of the antenna’s radiation pattern, where the energy is concentrated. For this particular antenna, if it’s on the roof and people are below it, their RF exposure will be less because the antenna radiates most energy horizontally rather than up and down.

My planned location for the antenna is on a mast, mounted above the second story roof, above my garage. Yes my garage is on the second story of my home. Ideally the mast would be as tall as possible, but to minimize the visual impact and possible neighbor complaints, I’ll be using a very short mast – about 1 foot. If someone were standing at the back of my garage for an extended period of time, they’d be about 5 feet below the antenna. This might be a small concern, although it still meets the MPE for controlled exposure even before considering all the mitigating factors just mentioned. Outside the garage, it’s impossible to get closer than about 13 feet to the antenna unless you’re standing on the roof. We should be fine.

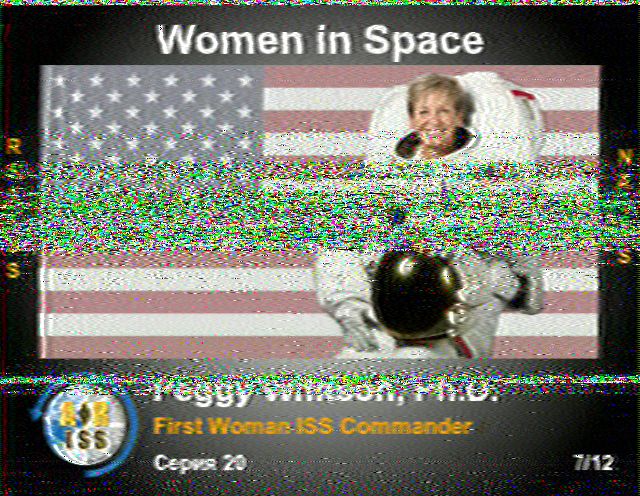

Read 11 comments and join the conversationInternational Space Station Downlink!

I downlinked a data transmission directly from the International Space Station! This amateur radio stuff is getting exciting. Using an orbital tracker tool, I found the time and location when the ISS would pass overhead here. From 9:16 AM to 9:21 AM, rising to the south, reaching its zenith to the southeast with 19 degrees elevation above the horizon, and setting to the east. I went to the top of a hill in my neighborhood, tuned my simple handheld radio to 145.800 MHz, pointed the antenna, and waited. And suddenly I heard crazy beeping! Dog walkers were staring.

Supposedly you should hold the antenna horizontally for best results, and perpendicular to the line to the ISS. But I just sort of waved the antenna around frantically, searching for the orientation that brought in the cleanest signal. I used the voice recorder app on my phone, holding the phone up to the radio speaker to record the beeping audio, while the wind made noise and cars drove by and the signal faded in and out. I captured almost all of one two-minute transmission and part of another, before the ISS went out of view. It was several minutes of recorded whistling and beeping.

Back home, I used some software called MMSSTV to decode the recorded audio, which was a PD120 slow-scan television image transmitted from the ISS, part of a special event celebrating women in space. The software provides options for tweaking the signal sync, phase, and image slant, because the Doppler shift screws up the signal when the ISS is moving by at 17500 miles per hour. Here’s the final decoded result. Peggy Whitson PhD, first woman ISS commander. Transmission received directly from Earth orbit, Sputnik style. Good morning!

Read 1 comment and join the conversationYellowstone Future Forecast

BMOW’s new Yellowstone Universal Disk Controller for Apple II computers has been popular in its first month of release. At the time of its announcement, I warned that parts supply constraints might make this the one and only manufacturing run of Yellowstone cards. That forecast now looks increasingly likely.

Ignoring the burst of Yellowstone sales immediately after its release, and extrapolating from the average daily sales rate more recently, there’s enough stock on hand to last until August or September. Unfortunately the Lattice FPGA at the heart of Yellowstone is out of stock everywhere, due to the global semiconductor shortage that keeps getting worse. The estimated factory lead time on new Lattice FPGAs is an eye-watering 67 weeks. Ouch!

I thought long and hard about placing an order anyway. After all, the sooner I place an order, the sooner I can eventually get the parts. But 67 weeks is a very long time, and that’s just an estimate. I’m not confident that Lattice really has any clue when they’ll be able to resume shipping these parts. It could be never.

Ultimately I decided I’m just not comfortable extending my plans until almost 2024. Will the other required Yellowstone parts still be available then, at prices to make the product viable? Will the product even still make sense to produce, or will it have been obsoleted by something else? Will I still be interested in this line of business in 2024? I’ve already invested money and time securing parts for planned future manufacturing runs of the Floppy Emu disk emulator and the ADB/USB Wombat input converter, expected roughly six months in the future. This already makes me nervous. 67 weeks “estimated” for the Lattice parts is just too much. That would demand making business plans on a cloud and a prayer.

This means when the current Yellowstone stock runs out this summer or fall, there won’t be any more inventory for a long time. I’ll keep an eye on the lead times for Lattice FPGAs and the other required parts. If the situation begins to improve, and it becomes possible to manufacture more Yellowstones with under 30 weeks lead time, I’ll consider jumping back in.

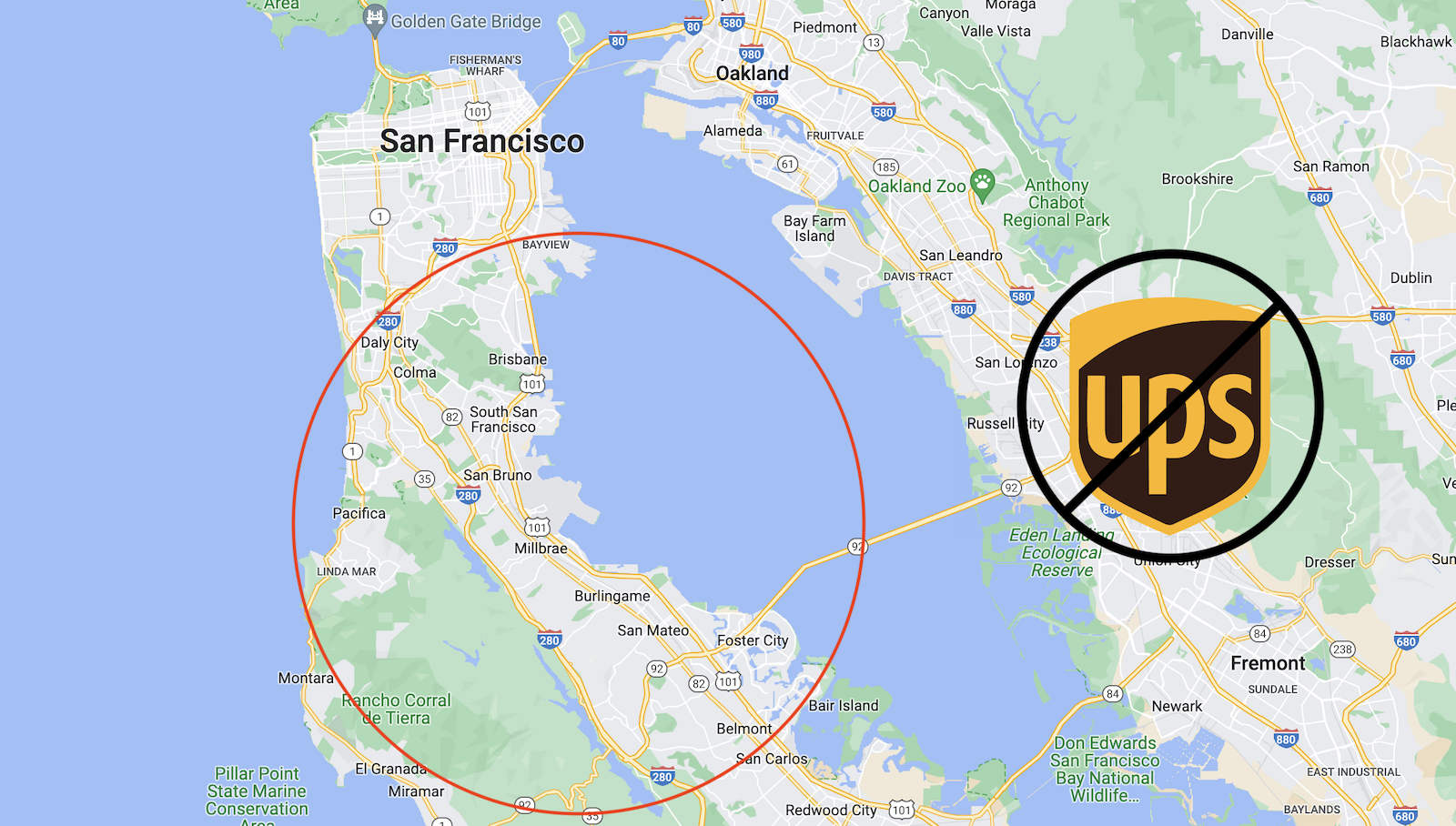

Read 7 comments and join the conversationUPS International Shipping Redlining in South San Francisco

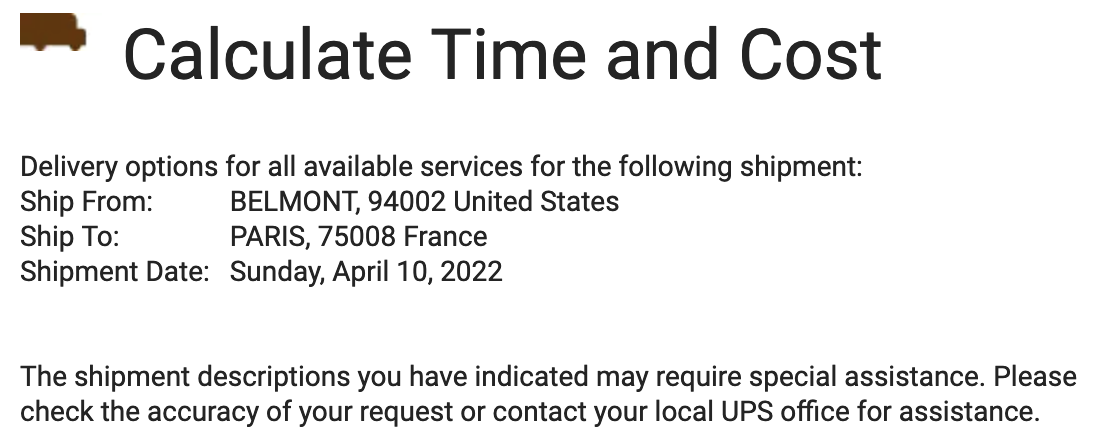

I’ve stumbled across a puzzling mystery. If you live in the southern part of the city of San Francisco, or in a large area further south into San Mateo County, UPS will not sell you international shipping labels. But change your Ship From zip code to a different city just a few miles away, and UPS will be happy to quote you for international shipping. I reached this conclusion after spending many hours pricing dummy international shipments with different Ship From and Ship To addresses, package sizes and weights, and content types. Only the Ship From address seems relevant. A UPS agent confirmed this behavior but couldn’t offer any explanation or solution.

I first discovered this problem on April 4, while using the third-party shipping service Pirate Ship to generate some UPS international shipping labels. For all my packages, Pirate Ship offered US Post Office shipping options, but nothing from UPS. After several hours working with Pirate Ship’s tech support, they concluded UPS was declining international shipping service to this region for some unknown reason. They told me to take up the issue with UPS.

Initially I didn’t believe Pirate Ship’s explanation, but then I discovered I could reproduce the same problem directly at the UPS.com page for international shipping quotes. You can try this too. Go to the UPS international shipment cost calculator page, as a guest (not logged in). Enter these package details:

Ship From: United States, Redwood City, zip code 94065. Or mostly anywhere else in the United States, except one of the redlined areas listed below.

Ship To: France, postal code 75008, Paris. Or try any another major city in Europe, Asia, wherever, it doesn’t matter.

Customs Value: 119

Package Details: My packaging, 11 x 9 x 2 inches, 0.8 pounds, 119 dollar value

You’ll see a list of available UPS shipping methods with specific price quotes. For example, UPS Worldwide Expedited service costs $154.44 to Paris. You’ll get the same behavior with Ship From addresses in most parts of California or elsewhere in the United States.

Now try the same experiment again, but for the Ship From location, choose one of the following cities and zip codes. These cities are a contiguous geographic region just south of San Francisco, centered around the San Francisco airport. The total population is about 1 million people.

94002 Belmont

94403 San Mateo

94402 San Mateo

94401 San Mateo

94404 Foster City

94010 Burlingame

94030 Millbrae

94128 San Francisco

94112 San Francisco

94132 San Francisco

94066 San Bruno

94080 South San Francisco

94019 Half Moon Bay

94044 Pacifica

94015 Daly City

94005 Brisbane

When you repeat the test using one of these Ship From addresses, UPS.com complains:

The shipment descriptions you have indicated may require special assistance. Please check the accuracy of your request or contact your local UPS office for assistance.

This is consistent with the apparent UPS international shipping redlining that I observed when using Pirate Ship. I spoke with the staff at the local UPS Store, but they’d never heard of this problem, and said their outgoing international shipments were working just fine. Through trial and error, I discovered that Shopify Shipping isn’t affected by this problem either, so it may have something to do with the class of UPS shipping account used to buy shipping labels. The problem definitely affects Pirate Ship, UPS.com’s own shipping quote system, and probably others too.

I then spent a long time on the phone with other UPS support agents who told me I was wrong, and that the Ship From zip code didn’t matter for determining international shipping service availability. On the third try, I was finally able to demonstrate the problem to a UPS agent, but she could only say “I don’t know why it’s doing that”. She couldn’t offer any explanation or solution. That was several days ago, and the problem is still happening today.

Read 5 comments and join the conversation