Computer History Museum Visit

A fantasy-land for hardware nerds like me is hidden in a former Silicon Graphics building in Mountain View, California. Despite living only a few miles away from the Computer History Museum, somehow I’d never found the time to visit there before today. It was well worth the visit, as the museum is stuffed to the roof with amazing artifacts from computing history. Even though the majority of the exhibits were closed due to a renovation project, I still got to see all kinds of wonderful techno-treasures.

Here I am standing inside the Cray-1 supercomputer. In 1976, this machine was as high-performance as you could get, a 250 MFLOPS monster that cost $5 million and required 115 kW of power.

Here I am standing inside the Cray-1 supercomputer. In 1976, this machine was as high-performance as you could get, a 250 MFLOPS monster that cost $5 million and required 115 kW of power.

I thought BMOW had a lot of wires, but brother, when I saw this Cray, my jaw dropped. Just look at this thing! See all that blue stuff on the inside? Those are individually-routed wires, stacks of wires, piles of wires, mountains of wires, every single one neatly-labeled with an ID code.

The Cray-1 is a hollow cylinder, about 6 feet tall, 4 feet in outside diameter, and 2 feet in inside diameter. Most of that space is consumed by about 2000 circuit boards, and the rest is positively stuffed with wires. I stared at the circuitry for a long time, trying to estimate the wiring density, and decided the machine has somewhere on the order of 100,000 individual wires.

Here’s a close-up, which gives you a sense of the massive scale of the wiring. It’s just insane.

Here’s a close-up, which gives you a sense of the massive scale of the wiring. It’s just insane.

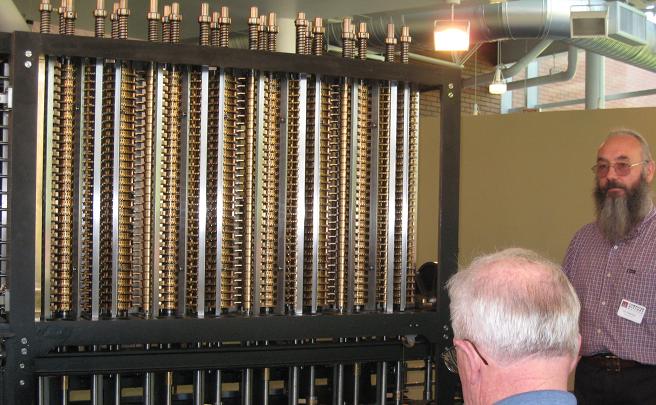

When I finished ogling wires, I took a look at Babbage’s Difference Engine No. 2. Designed by Charles Babbage in the 19th century, this massive mechanical marvel computes tables of polynomials. It supports up to 7th-order polynomials, and computes results to 30 decimal places. The desired polynomial is entered by setting a series of gears, and then a crank is turned by hand to generate the results, one at a time. Babbage designed it all on paper, and built working versions of small pieces of the mechanism, but it remained a purely theoretical invention for more than a century after his death. Some doubts remained about whether the machine would actually have worked, had it been built.

In 1985, the Science Museum in London set out to build a working Difference Engine No. 2, from Babbage’s original design drawings. The project took 17 years to complete, facing all sorts of setbacks, but in the end the machine worked as Babbage had intended. The finished difference engine is on display at London’s Science Museum, but a duplicate was made for project benefactor and Microsoft millionaire Nathan Myhrvold. Myhrvold agreed to lend his duplicate to the Computer History Museum, to share and educate.

Some of the other computing artifacts I got to see:

- Deep Blue, the IBM chess computer that defeated World Chess Champion Garry Kasparov in 1997.

- The first mouse- a block of wood with a momentary push switch mounted on it. Created by Doug Engelbart at PARC in 1964.

- A 10MB hard disk platter, 3 feet in diameter, from 1974.

- An original Apple I, the kit-built ancestor of the Apple II. A hand-assembled logic board, keyboard, and power supply, mounted on a plywood plank.

- A restored and working PDP-1. During the restoration, volunteers were able to retrieve data originally stored in the core memory decades earlier.

Too much awesome stuff!

Read 1 comment and join the conversation1 Comment so far

Leave a reply. For customer support issues, please use the Customer Support link instead of writing comments.

The demo of the difference engine is just so beautiful! I love the clang-click it makes as each result is computed and seeing the carry arms spiral around.

This museum is a definite must see!